Editorial

EditorialIn his interview this issue Bernard Caleo suggests that we are “at a really interesting point where we are about to swing into a new, greater appreciation of the [graphic story] medium”. Whilst I don’t know if I share his belief that we are quite at the tipping point, I have noted in these pages, over past issues, that there has been an encouraging interest in the medium by local book publishers, which has sparked and equally heartening number of articles and reviews in the mass media.

Recently the Australian has run two pieces that are worthy of comment. The first of these, “Picture this: the future of fiction” (Australian Literary Review 1/4/09), by long time student of the form Cefn Ridout, is an astute look at recent publications, both here and abroad, wrapped up in a longitudinal commentary on the medium’s development worldwide. The second “In a superhero-free world” by Fiona Gruber (5/5/09) was written to mark the launch of Gestalt’s Flinch anthology (review next issue), but also to highlight a new Star Wars storyline produced by local creators, and Flinch contributors, Tom Taylor and Colin Wilson.

Whilst these are positive pieces, they are still both variants on the ‘comics grow up’ articles that have been appearing in the mass media for at least the last twenty-five years. Whilst it is gratifying that the media is willing to acknowledge that the medium is capable of a wide range of subjects, I can’t help wondering if it isn’t time for a change of tack; essentially for articles on comics to ‘grow up’, or beyond, the ‘comics grow up’ angle.

Back in the 1970s the only sort of article you were likely to get out of the mass media regarding comics was one slanted to their collectability. A favoured question of journalists then was “Do you read them, or just collect them?” Moreover, the journalists appeared to have their angle already worked out and were just looking for some appropriate quotes to slot in. If you tried to move the interview into other areas, like how not all comics were for kids, you were likely to get a short shrift.

An example of this is an article in a suburban news-paper from 1981. As well as some wildly skewed text, it contained a photo of my then partner in Minotaur and Inkspots, Colin Paraskevas, standing in front of the new comic racks at Minotaur holding a copy of Inkspots 2. Colin’s intention was to try and get some publicity for either the publication or store, but the journalist had other ideas. The article made no mention of either entity and captioned the photo “Comics have always held a strange fascination for Colin Paraskevas.”!

Not long after this, in I think 1983, the Age ran the first of the ‘comics grow up’ articles that I can recall seeing. Penned by the budding journo Richard Guilliat, who has gone on to make a name for himself as an investigative journalist mainly for the Sydney Morning Herald, it primarily used a then current story line in Captain America that had, I think, something to do with corruption in high places, to demonstrate that comics could deal with more ‘serious’ themes.

As the 1980s progressed, and more significant changes were wrought in the medium by the likes of Miller, Moore and the Bros Hernandez, these articles began to appear more frequently, both here and abroad. Whilst it is pleasing that some journalists had realised that not all comics were either for kids, or the preserve of collectors, these articles still marked the medium out as in some way separate from most other creative art-forms. Reviews of new plays or poetry collections, for example, do not generally contain a complete history of the form. There is an assumption that the reader, even if they don’t have a complete knowledge of the medium’s development, can still appreciate a new work regardless.

In that way I find the slant of Gruber’s article refreshing in it’s willingness to only give a smattering of the back-story and instead to concentrate on the specifics at hand. This is not to criticise Ridout. Having written my fair share of these sorts of articles over the years I know that the ‘comics grow up’ angle is a convenient hook on which to hang an article. Further, I realise that it is only natural to want to use your knowledge of the medium in an endeavour to make a favourable impression on the casual reader. But I still look forward to the time when comics are treated like any other art form. That, at least, may be in the process of occurring.

Recently the Australian has run two pieces that are worthy of comment. The first of these, “Picture this: the future of fiction” (Australian Literary Review 1/4/09), by long time student of the form Cefn Ridout, is an astute look at recent publications, both here and abroad, wrapped up in a longitudinal commentary on the medium’s development worldwide. The second “In a superhero-free world” by Fiona Gruber (5/5/09) was written to mark the launch of Gestalt’s Flinch anthology (review next issue), but also to highlight a new Star Wars storyline produced by local creators, and Flinch contributors, Tom Taylor and Colin Wilson.

Whilst these are positive pieces, they are still both variants on the ‘comics grow up’ articles that have been appearing in the mass media for at least the last twenty-five years. Whilst it is gratifying that the media is willing to acknowledge that the medium is capable of a wide range of subjects, I can’t help wondering if it isn’t time for a change of tack; essentially for articles on comics to ‘grow up’, or beyond, the ‘comics grow up’ angle.

Back in the 1970s the only sort of article you were likely to get out of the mass media regarding comics was one slanted to their collectability. A favoured question of journalists then was “Do you read them, or just collect them?” Moreover, the journalists appeared to have their angle already worked out and were just looking for some appropriate quotes to slot in. If you tried to move the interview into other areas, like how not all comics were for kids, you were likely to get a short shrift.

An example of this is an article in a suburban news-paper from 1981. As well as some wildly skewed text, it contained a photo of my then partner in Minotaur and Inkspots, Colin Paraskevas, standing in front of the new comic racks at Minotaur holding a copy of Inkspots 2. Colin’s intention was to try and get some publicity for either the publication or store, but the journalist had other ideas. The article made no mention of either entity and captioned the photo “Comics have always held a strange fascination for Colin Paraskevas.”!

Not long after this, in I think 1983, the Age ran the first of the ‘comics grow up’ articles that I can recall seeing. Penned by the budding journo Richard Guilliat, who has gone on to make a name for himself as an investigative journalist mainly for the Sydney Morning Herald, it primarily used a then current story line in Captain America that had, I think, something to do with corruption in high places, to demonstrate that comics could deal with more ‘serious’ themes.

As the 1980s progressed, and more significant changes were wrought in the medium by the likes of Miller, Moore and the Bros Hernandez, these articles began to appear more frequently, both here and abroad. Whilst it is pleasing that some journalists had realised that not all comics were either for kids, or the preserve of collectors, these articles still marked the medium out as in some way separate from most other creative art-forms. Reviews of new plays or poetry collections, for example, do not generally contain a complete history of the form. There is an assumption that the reader, even if they don’t have a complete knowledge of the medium’s development, can still appreciate a new work regardless.

In that way I find the slant of Gruber’s article refreshing in it’s willingness to only give a smattering of the back-story and instead to concentrate on the specifics at hand. This is not to criticise Ridout. Having written my fair share of these sorts of articles over the years I know that the ‘comics grow up’ angle is a convenient hook on which to hang an article. Further, I realise that it is only natural to want to use your knowledge of the medium in an endeavour to make a favourable impression on the casual reader. But I still look forward to the time when comics are treated like any other art form. That, at least, may be in the process of occurring.

Interview

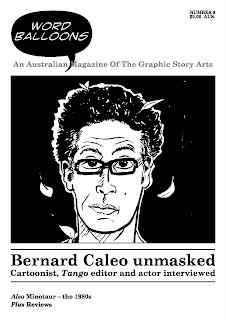

“Formally I’m qualified to talk about Tintin, that’s it.”

An interview with Bernard Caleo.

Conducted by Philip Bentley, April 2009.

Prior to this interview I would have described Bernard Caleo as a trained actor with a great passion for comics. But as a consequence of our discussion, I see that the opposite is, technically, more accurate. Regardless, though, ‘passion’ is a most appropriate word when talking about him.

Bernard is a great advocate for the graphic story medium, both in this country and generally. Through his own strips, either alone or in collaboration, his editorship of the anthology Tango, or even some of his theatrical work, Bernard seeks to convey his love of the medium, both to fellow aficionados and to the general public.

In this interview I seek to explore his roots, his collective oeuvre, his publishing ethos for Tango, his theatrical leanings, both his ‘day job’ as an ‘applied’ actor and his singular two-man play based on Alan Moore’s comic Miracleman , and finally the parallels between comics and the theatre.

In this interview I seek to explore his roots, his collective oeuvre, his publishing ethos for Tango, his theatrical leanings, both his ‘day job’ as an ‘applied’ actor and his singular two-man play based on Alan Moore’s comic Miracleman , and finally the parallels between comics and the theatre.

Excerpt

PB: So when and how did the notion to produce your own comic arise?

BC: Towards the end of the 1980s I was broadening my interests in comics. Then I fell in love. In 1990 my girlfriend went to England and I followed. Rather than just occupying myself with being in love, I decided I should do something while I was over there. I found an ad for the London Cartoon Centre who were offering a ten week course. So I wrote a letter in strip format, and they replied saying “Why not”.

PB: What was the course like?

BC: There was a lot of basic stuff about page layout, photo-copying technique, brushes and nibs. But it was also a prod towards doing your own comics. And that’s when I really began to join some dots about how comics are a great way to tell stories. Significant for the ideas about creating comics that were buzzing around in my head, was the friendship I had made with this guy, Brendan Tolley, [who I had] met at a life-drawing class just before I left Australia. It was clear from the beginning that he was a strong draughtsman. During my time in London we had a constant communication via weekly letters, this being the time before email. Both of us were awash in ‘heartbreak soup’, to borrow Gilbert Hernandez’s phrase. During one of my rambling letters to him I suggested that we should collaborate on a story set in Melbourne. I have always been fascinated by the city as a place, as an architecture, as a culture, as an idea, as an history. So that’s how the Yell Olé! strip began to develop. When I got back, sans girlfriend, I had plenty of time on my hands and a lot of energy to devote to a project. So we leapt into it. At it’s heart it was a strip that was trying to mythologise, to enshrine, to explore the shape, the physical material of Melbourne.

PB: It was clearly trying to deal with issues relevant to a spirit of place split into two loci: the city in Yell Olé! and the country in The False Impressionists [the succeeding series].

BC: And The False Impressionists is rooted in more of an historical perspective. It’s attempting to be a White Man’s Dreaming sort of story.

***

PB: You are probably best known for editing Tango, a somewhat annual anthology of romance strips. How did that come about?

BC: In 1996, Tolley and I were part of a zines and comics exhibition that was part of the Melbourne Fringe Festival. There were a couple of parallel publications, one of which basically contained rants by the various creators. I was asked to write something on the intersection of comics and zines and by the end of my rant I had painted myself into a corner. I had defined the difference between comics and zines, then said that I thought comics had a great future in this country as they weren’t hidebound by genres as comics in other countries are. Then I said that, since the demise of the great anthology Fox Comics, and in the absence of any ongoing anthology, what we needed was a new one, and that somebody should do that. I then realised that that somebody probably needed to be me.

PB: One of the most notable things about Tango is that it includes work by people from outside the established comics community and sees this, I gather, as part of its mission statement.

BC: Absolutely. In the course of writing that essay I had decided that what we needed was a book that showcased Australian comic work. But not just by people in the established comic culture. If you were a songwriter and you wanted to have a bash at comics I was interested. I wanted that interchange of ideas because I see that as one of the steps to developing a more robust comic culture. To bring people in and help them fall in love with the medium.

PB: Whilst that may be one of its strengths, it also could be said to be one of its weaknesses, as you have experienced comic creators rubbing shoulders with neophytes who are learning as they go.

BC: Tango was never set up to be the best of Australian comic book makers. That leads to its unevenness, but also, in my mind, to its charm. It’s very accepting, it’s very embracing. For me, it’s an important part of the texture of Tango.

PB: There’s going to be a best of Tango coming out from Allen & Unwin. I’m interested in hearing the selection criteria. Are they going to be the same as Tango regular?

BC: We’re actually changing the title to The Tango Collection because I felt the draft title ‘The Best of Tango’ cut across the ethos of the anthology. It will be around 200pp released in December 2009 and will feature stories from the first eight issues. I hope to have the next ‘ordinary’ issue (Tango 9: Love and War) out around the same time to capitalise on cross-promotion. Erica Wagner, who is the publisher at A&U in charge of the graphic novel push, will have a hand in the selection, as will the editor Elise Jones. I have provided a rough cut of strips, they have said yes yes yes, no no no, and then I have provided more names, and so on.

***

PB: You mentioned that you acted at University.

BC: I started out doing a Science Degree in 1986 and ended up with an Arts Degree in 1994. Really, I spent only a minimal amount of time studying during that period. Most of my time was spent in the Theatre Department, which is an elective facility like the Sports Union. I basically just did show after show after show because I loved it; the milieu and the people. Out of that came many great friendships, lovers etc. One friendship, in particular, was with Bruce Woolley. I introduced him to comics and he introduced me to various aspects of theatre. He had trained in the Lecoq style of theatre making. That is a French form that goes beyond purely acting, incorporating elements of puppetry, music and multi-media. And it was that training that made Bruce say, when he was reading Miracleman, “Hey Bernard we can make a great play out of this.” To which I replied “Bruce…you’re absolutely out of your mind! It’s a superhero comic book; it’s got flying people and bombs. You can’t do that sort of thing on stage.” So naturally we did.

PB: I have to say that initially I was dubious, but to your credit, with little more than a couple of dodgy wigs and some stackable boxes, you make the audience ‘believe that a man can fly’. This despite the issue of copyright, in which it must be the most complicated comic title ever.

[The saga of Miracleman is long and winding and readers interested in following it twists and turns are encouraged to access the Wikepedia entry.] It works because you take an unlikely situation and make it succeed by turning the perceived weakness into strengths. By taking a deliberately low-tech approach it becomes part of the process. But it’s clever how it is part spoof, part homage. The respect you feel for the work comes through. I think it’s the most successful thing of yours that I’ve seen.

The rest of the interview can be found in Word Balloons 9.

PB: So when and how did the notion to produce your own comic arise?

BC: Towards the end of the 1980s I was broadening my interests in comics. Then I fell in love. In 1990 my girlfriend went to England and I followed. Rather than just occupying myself with being in love, I decided I should do something while I was over there. I found an ad for the London Cartoon Centre who were offering a ten week course. So I wrote a letter in strip format, and they replied saying “Why not”.

PB: What was the course like?

BC: There was a lot of basic stuff about page layout, photo-copying technique, brushes and nibs. But it was also a prod towards doing your own comics. And that’s when I really began to join some dots about how comics are a great way to tell stories. Significant for the ideas about creating comics that were buzzing around in my head, was the friendship I had made with this guy, Brendan Tolley, [who I had] met at a life-drawing class just before I left Australia. It was clear from the beginning that he was a strong draughtsman. During my time in London we had a constant communication via weekly letters, this being the time before email. Both of us were awash in ‘heartbreak soup’, to borrow Gilbert Hernandez’s phrase. During one of my rambling letters to him I suggested that we should collaborate on a story set in Melbourne. I have always been fascinated by the city as a place, as an architecture, as a culture, as an idea, as an history. So that’s how the Yell Olé! strip began to develop. When I got back, sans girlfriend, I had plenty of time on my hands and a lot of energy to devote to a project. So we leapt into it. At it’s heart it was a strip that was trying to mythologise, to enshrine, to explore the shape, the physical material of Melbourne.

PB: It was clearly trying to deal with issues relevant to a spirit of place split into two loci: the city in Yell Olé! and the country in The False Impressionists [the succeeding series].

BC: And The False Impressionists is rooted in more of an historical perspective. It’s attempting to be a White Man’s Dreaming sort of story.

***

PB: You are probably best known for editing Tango, a somewhat annual anthology of romance strips. How did that come about?

BC: In 1996, Tolley and I were part of a zines and comics exhibition that was part of the Melbourne Fringe Festival. There were a couple of parallel publications, one of which basically contained rants by the various creators. I was asked to write something on the intersection of comics and zines and by the end of my rant I had painted myself into a corner. I had defined the difference between comics and zines, then said that I thought comics had a great future in this country as they weren’t hidebound by genres as comics in other countries are. Then I said that, since the demise of the great anthology Fox Comics, and in the absence of any ongoing anthology, what we needed was a new one, and that somebody should do that. I then realised that that somebody probably needed to be me.

PB: One of the most notable things about Tango is that it includes work by people from outside the established comics community and sees this, I gather, as part of its mission statement.

BC: Absolutely. In the course of writing that essay I had decided that what we needed was a book that showcased Australian comic work. But not just by people in the established comic culture. If you were a songwriter and you wanted to have a bash at comics I was interested. I wanted that interchange of ideas because I see that as one of the steps to developing a more robust comic culture. To bring people in and help them fall in love with the medium.

PB: Whilst that may be one of its strengths, it also could be said to be one of its weaknesses, as you have experienced comic creators rubbing shoulders with neophytes who are learning as they go.

BC: Tango was never set up to be the best of Australian comic book makers. That leads to its unevenness, but also, in my mind, to its charm. It’s very accepting, it’s very embracing. For me, it’s an important part of the texture of Tango.

PB: There’s going to be a best of Tango coming out from Allen & Unwin. I’m interested in hearing the selection criteria. Are they going to be the same as Tango regular?

BC: We’re actually changing the title to The Tango Collection because I felt the draft title ‘The Best of Tango’ cut across the ethos of the anthology. It will be around 200pp released in December 2009 and will feature stories from the first eight issues. I hope to have the next ‘ordinary’ issue (Tango 9: Love and War) out around the same time to capitalise on cross-promotion. Erica Wagner, who is the publisher at A&U in charge of the graphic novel push, will have a hand in the selection, as will the editor Elise Jones. I have provided a rough cut of strips, they have said yes yes yes, no no no, and then I have provided more names, and so on.

***

PB: You mentioned that you acted at University.

BC: I started out doing a Science Degree in 1986 and ended up with an Arts Degree in 1994. Really, I spent only a minimal amount of time studying during that period. Most of my time was spent in the Theatre Department, which is an elective facility like the Sports Union. I basically just did show after show after show because I loved it; the milieu and the people. Out of that came many great friendships, lovers etc. One friendship, in particular, was with Bruce Woolley. I introduced him to comics and he introduced me to various aspects of theatre. He had trained in the Lecoq style of theatre making. That is a French form that goes beyond purely acting, incorporating elements of puppetry, music and multi-media. And it was that training that made Bruce say, when he was reading Miracleman, “Hey Bernard we can make a great play out of this.” To which I replied “Bruce…you’re absolutely out of your mind! It’s a superhero comic book; it’s got flying people and bombs. You can’t do that sort of thing on stage.” So naturally we did.

PB: I have to say that initially I was dubious, but to your credit, with little more than a couple of dodgy wigs and some stackable boxes, you make the audience ‘believe that a man can fly’. This despite the issue of copyright, in which it must be the most complicated comic title ever.

[The saga of Miracleman is long and winding and readers interested in following it twists and turns are encouraged to access the Wikepedia entry.] It works because you take an unlikely situation and make it succeed by turning the perceived weakness into strengths. By taking a deliberately low-tech approach it becomes part of the process. But it’s clever how it is part spoof, part homage. The respect you feel for the work comes through. I think it’s the most successful thing of yours that I’ve seen.

The rest of the interview can be found in Word Balloons 9.

Article

My Life in Comics Part VII: Minotaur–the 1980s

by Philip Bentley

In this instalment I deal with the saga of Minotaur from the opening of the first shop in 1980, though five relocations, to when I left the business at the end of 1989. As with my recollections on the latter days of Inkspots it is a salutary tale of how naïve idealism can be put to the sword on the altar of commercial enterprise.

by Philip Bentley

In this instalment I deal with the saga of Minotaur from the opening of the first shop in 1980, though five relocations, to when I left the business at the end of 1989. As with my recollections on the latter days of Inkspots it is a salutary tale of how naïve idealism can be put to the sword on the altar of commercial enterprise.

Excerpt

In the last chapter, I detailed how in 1977 Greg Gates, Colin Paraskevas and myself established the Melbourne comic retailer Minotaur. Although initially begun as a mail order concern, our plans had always been to progress to a shop when it had grown larger and we had resolved the issue of where it would be best located. The city centre had always seemed the optimum position, but we feared the higher rents here would be prohibitive, and we were unsure if an inner-city shop could draw customers from all suburbs.

It was Colin who solved this conundrum, suggesting we investigate warehouse space in the city centre that could double as a retail establishment. Admittedly, the first few places we looked at were less than inspiring but then we found a ground floor location in Tattersalls Lane, a small thoroughfare running between Little Bourke and Lonsdale Streets, between Swanston and Russell. Housed in a crumbling tenement, whose upper three floors contained artists’ studios, it was centrally located without commanding a premium rent.

The premises opened for business on Thursday 11 September 1980 and initially traded Thursday to Saturday. For customers we relied on circulating our mail order clientele, word of mouth and some small ads placed on the comics page of the Sun. This was never going to produce a stampede, but numbers and sales did gradually climb over the initial weeks and months.

Although I had my reservations about the premisis due to it’s crumbling nature, to a person any former customers I have spoken to regarding these times remember the location fondly. They equate the circulative route one had to take to gain access – up the lane, into the stair-well, through the fire door to the shared lobby and finally into the shop – as akin to following the fabled labyrinth to a cavernous treasure trove. And certainly there were many unusual items displayed; the product of three years sourcing stock from around the world: commercial comics both old and new, alternative comics in a variety of formats, French albums, fanzines, art books, prints and portfolios.

***

We moved to the Mid City Arcade in May 1981. We would be there a bit under two years: another nine months in the original shop (16) and about a year over the arcade in a double shop (11 & 12). In mid-1982 we re-opened shop 16, initially to sell rock books and records, then, after the latter proved to be not a success, added a range of books and merchandise about films and TV series with an SF or adventure slant. By early 1983, though, even with two stores, Mid City Arcade was becoming too small for us. So when Colin spotted an old pizza restaurant for rent in Swanston Street, between Little Bourke and Lonsdale Streets, it wasn’t long before we were engaging in another round of renovations and removals.

The rest of the article can be found in Word Balloons 9.

In the last chapter, I detailed how in 1977 Greg Gates, Colin Paraskevas and myself established the Melbourne comic retailer Minotaur. Although initially begun as a mail order concern, our plans had always been to progress to a shop when it had grown larger and we had resolved the issue of where it would be best located. The city centre had always seemed the optimum position, but we feared the higher rents here would be prohibitive, and we were unsure if an inner-city shop could draw customers from all suburbs.

It was Colin who solved this conundrum, suggesting we investigate warehouse space in the city centre that could double as a retail establishment. Admittedly, the first few places we looked at were less than inspiring but then we found a ground floor location in Tattersalls Lane, a small thoroughfare running between Little Bourke and Lonsdale Streets, between Swanston and Russell. Housed in a crumbling tenement, whose upper three floors contained artists’ studios, it was centrally located without commanding a premium rent.

The premises opened for business on Thursday 11 September 1980 and initially traded Thursday to Saturday. For customers we relied on circulating our mail order clientele, word of mouth and some small ads placed on the comics page of the Sun. This was never going to produce a stampede, but numbers and sales did gradually climb over the initial weeks and months.

Although I had my reservations about the premisis due to it’s crumbling nature, to a person any former customers I have spoken to regarding these times remember the location fondly. They equate the circulative route one had to take to gain access – up the lane, into the stair-well, through the fire door to the shared lobby and finally into the shop – as akin to following the fabled labyrinth to a cavernous treasure trove. And certainly there were many unusual items displayed; the product of three years sourcing stock from around the world: commercial comics both old and new, alternative comics in a variety of formats, French albums, fanzines, art books, prints and portfolios.

***

We moved to the Mid City Arcade in May 1981. We would be there a bit under two years: another nine months in the original shop (16) and about a year over the arcade in a double shop (11 & 12). In mid-1982 we re-opened shop 16, initially to sell rock books and records, then, after the latter proved to be not a success, added a range of books and merchandise about films and TV series with an SF or adventure slant. By early 1983, though, even with two stores, Mid City Arcade was becoming too small for us. So when Colin spotted an old pizza restaurant for rent in Swanston Street, between Little Bourke and Lonsdale Streets, it wasn’t long before we were engaging in another round of renovations and removals.

The rest of the article can be found in Word Balloons 9.

Also reviews of Black House’s The Twilight Age 0 & 1 by Jan Scherpenhuizen “the narrative and layouts are competently handled, but both pencils and inks display an inconsistent level of quality”, The Dark Detective: Sherlock Holmes 0 by Chris Sequiera, Tim McEwan & Phil Cornell “there is no denying the verve with which the work is produced.”, and Pat Grant’s Lumpen Proletariat 5 “his stories are funny and engaging, his art detailed yet clear”.